Born 1898 Died 1918

Today, 24 October 2018, marks exactly 100 years since my great uncle, Private Arthur McArdle of the 2nd Battalion of the Lincolnshire Regiment, lost his life on the battlefields of World War 1.

Back in April, on ANZAC Day, to be exact, I posted a sort of memorial to another great uncle – my grandfather’s younger brother, Edward Butler – who also made the ultimate sacrifice in World War I . Today’s memorial is to my grandmother‘s younger brother. I find it very sad to know that this married couple each suffered the loss of a younger brother in WW1. I suppose they would at least have had empathy for each other.

Honouring Private Arthur McArdle

Like Edward, Arthur lost his life in that last horrible year of World War I. But even sadder than Edward’s death at the age of 27, Arthur, aged just 20, was killed on 24 October 1918 – merely 18 days before the end of the war. Eighteen days. The difference between life and death. He was so close to being called home. He wouldn’t have known it, but he just had to stay alive for another eighteen days.

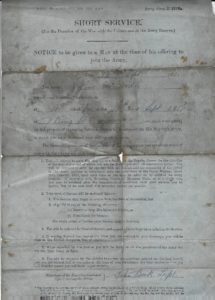

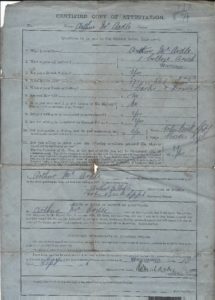

Like my great uncle Edward, I know very little about Private A McArdle, No. 42584, 2nd Battalion of the Lincolnshire Regiment, although from his enlistment notice I’ve worked out that he was probably born on 8 September 1898 – he was 17 years and 361 days old when he signed up for ‘Short Service’ on 12 September 1916. (Of course, 1916 was a leap year, so it’s also feasible he was born on 11 September 1916.) He was unmarried, lived at 1 College Arch, Whitehaven in Cumberland (now Cumbria) and worked as a ‘Carter and Driver’.

Arthur laid to rest

I believe Arthur is buried at Delsaux Farm Cemetery, Beugny, in northern France. And following his death, the War Office paid my grandmother Rose Ann (McArdle) Butler – his oldest sister – compensation of £13 10/6, including a ‘War Gratuity’ of £9. His mother and father passed away in 1912 and 1916 respectively, and his eldest brother, John, was living in Bisbee, Arizona, at this stage, so his sister would have probably been noted as next of kin.

Arthur’s nephew

Interestingly, Arthur’s sister (my grandmother), Rose Ann (McArdle) Butler, gave birth to a baby boy in 1916 and named him Arthur, presumably in honour of her little brother, the baby’s uncle. Sadly, Arthur’s young namesake would battle polio as a child and only live until 36 years of age, passing away in 1950. Sadly, it seems no-one in the family was meant to be named ‘Arthur’.

War is a mongrel, no doubt about it. I can’t imagine how hard it must have been for my grandparents to each lose a younger sibling in that last, horrible year of World War 1. Ironically – and I only just realised this today – both Arthur and his sister’s brother-in-law, Edward Butler, served in the 2nd Battalion of the Lincolnshire Regiment. Same regiment, died six months apart.

And like Edward, Arthur died ‘without issue’ (i.e. leaving no children) and so very few people today are award he even existed. Will anyone remember either of them in a hundred years’ time?

Vale, Great Uncle Arthur. And thank you (and Edward) for making the ultimate sacrifice so that I and others like me could have the lives that we have today. I’m sorry neither of you had that chance.